ISQ - April 2024

Key Takeaways

The two most hot-button topics for consumers are food and energy—both are highly visible. Since everyone has to eat, food tends to outweigh energy in economic importance.

The building blocks of the global food chain are the four staple crops—corn, wheat, rice and sugarcane.

The wheat market has been the most influenced by geopolitics in recent years, because Russia is the world’s third-largest producer, and Ukraine is (or rather was) the sixth. When Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, wheat prices spiked to an unprecedented $11/bushel.

Wheat prices are currently at three-year lows – even lower than they had been just prior to the war – and corn prices have also fallen sharply.

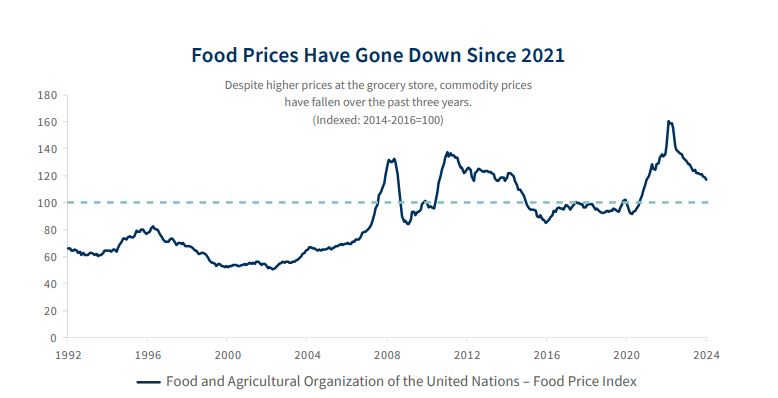

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organisation’s Food Price Index started 2024 at 118, down 10% from one year ago, and with an even steeper decline versus 2022.

What does inflation mean to you? For a typical consumer, the two most hot-button topics are food and energy. Both play a significant role in household spending, and just as importantly, both are highly visible. Petrol prices are noticed every time a driver fills up at the pump, and food prices are front and centre during every visit to a grocery store. Bearing in mind that everyone needs to eat, whereas it is almost possible to avoid spending on fuel, food tends to outweigh energy in economic importance. In the US Consumer Price Index, for example, food and energy are weighted at approximately 14% and 8%, respectively. While the media likes to write about Big Macs and cartons of eggs as indicators of food cost inflation, the building blocks of the global food chain are staple crops. Human consumers aside, some of the most important crops are also vital as animal feed. In this article, we will take a look at the world’s top four crops by volume: sugarcane, corn (maize), rice, and wheat.

To the extent that we think about crops, we are most familiar with corn—for one thing, they put it in the gasoline tank! Consider this, practically all of the fuel-grade ethanol blended into US gasoline is derived from corn. Corn is also the predominant US source of animal feed. Interestingly enough, only 1% of U.S. corn supply is sweet corn, which is what’s sold in the supermarket. The US is the world’s largest corn producer, accounting for nearly one-third of global supply, or as much as second-ranked China and third-ranked Brazil combined. Corn prices fell this past February to their lowest levels since late 2020, around $4/bushel, down from a high of $8/ bushel in mid-2022. This is obviously unwelcome news for farmers in the Midwest’s Corn Belt, but it is good news for cattle ranchers and, by extension, anyone who enjoys a good steak. US corn plantings in 2023 were up six million acres to a near record 95 million acres—this means more supply in 2024. The US Department of Agriculture forecasts a decline to 91 million acres in 2024, which shows a response to the lower prices.

Bearing in mind that US ethanol volumes have been flattish over the past decade, to the extent that US farmers are incentivised to produce more corn, it is to ship abroad. China is the world’s largest corn importer, followed by Japan—in both countries, corn is important for animal feed. China’s own corn production has plateaued, so all of its incremental demand needs to come from imports. Historically, China used to import almost entirely from the US, but that is changing. After the Chinese government approved purchases from Brazil in 2022, imports from the US fell by roughly half. While there are some political overtones here vis-à-vis the complicated relationship between Washington and Beijing, it is also a fact that Latin American corn tends to be cheaper than that which comes from Iowa or Kansas.

The wheat market has been the most influenced by geopolitics in recent years, because Russia is the world’s third-largest producer, and Ukraine is (or rather was) sixth-ranked. When Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, wheat prices spiked to an unprecedented $11/bushel. As with corn, prices have dropped by half since then and are currently at three-year lows—in other words, even lower than they had been just prior to the war. Recall, one of Russia’s tactics in the early months of the war had been to impose a blockade of Ukrainian ports, thus halting the export of wheat. In response to intense pressure from African and Middle Eastern countries that depend on this wheat, Russia agreed to allow the resumption of Ukrainian exports in mid-2022. Although one year later this deal fell apart, Ukraine is still exporting via the Black Sea, bearing in mind 1) the weakness of Russia’s navy; and 2) it is difficult to envision the Kremlin making a political decision to attack international civilian ships carrying grain. Ukraine is also shipping some wheat overland into Europe. Although supply from Ukraine is still impacted by the war, there is no longer fear of outright shortages.

The top nine rice-producing countries are all in Asia, led by China and India. Although China produces twenty times more rice than the US, it still relies on a significant amount of imports. India, on the other hand, had historically been a rice-exporting country. That changed in 2022, when, in response to concerns about domestic food security, India’s government banned the export of what’s known as broken rice. In 2023, the ban was broadened to encompass plain, white, long-grain rice. In large part because of the absence of Indian rice on the global market, current prices near $19/hundredweight are at three-year highs and double what they were in 2020. It is understandable that India’s policymakers are prioritising more supply for their own citizens, but the flip side is higher prices in China and other import-dependent countries.

It is an underappreciated fact that sugarcane is the world’s largest staple crop by volume. The sugarcane market is also interesting for the extent to which it is dominated by a single country: Brazil accounts for 40% of global production, even more than the US proportion of the corn market. Much like corn in the US, sugarcane plays a central role in Brazilian ethanol supply. Specifically, what’s known as sugarcane bagasse—the fibrous, dry part of the plant—is used to generate electricity. Also, needless to say, it is hard to imagine a 21st century food system without large amounts of sugar—so much so that public health professionals have been sounding the alarm. In any case, while the sugar market has faced the challenge of periodic Brazilian droughts over the past decade, it is the second-largest producer—India—which explains why prices have doubled since 2020 to around $0.25/pound. As was the case with rice, India banned sugar exports in 2023, which means supply from Brazil is even more crucial than before.

Putting everything together, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organisation’s Food Price Index started 2024 at 118, down 10% from one year ago, and with an even steeper decline versus 2022. Bottom line: good news for consumers. Let’s underscore that food constitutes a larger proportion of spending in lower-income communities compared to wealthier ones, and in emerging markets compared to industrialised economies. Lower food prices open the door to more discretionary spending and, at a macro level, alleviate inflationary pressures and thus support monetary easing by central banks.

Issued by Raymond James Investment Services Limited (Raymond James). The value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up, and you may not recover the amount of your original investment. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. Where an investment involves exposure to a foreign currency, changes in rates of exchange may cause the value of the investment, and the income from it, to go up or down. The taxation associated with a security depends on the individual’s personal circumstances and may be subject to change.

The information contained in this article is for general consideration only and any opinion or forecast reflects the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates, Inc. as at the date of issue and is subject to change without notice. You should not take, or refrain from taking, action based on its content and no part of this article should be relied upon or construed as any form of advice or personal recommendation. The research and analysis in this article have been procured, and may have been acted upon, by Raymond James and connected companies for their own purposes, and the results are being made available to you on this understanding. Neither Raymond James nor any connected company accepts responsibility for any direct or indirect or consequential loss suffered by you or any other person as a result of your acting, or deciding not to act, in reliance upon such research and analysis.

If you are unsure or need clarity upon any of the information covered in this article please contact your wealth manager.

APPROVED FOR CLIENT USE