ISQ - April 2024

Key Takeaways

Saying ‘this time is different’ is fitting in trying to understand the economy since the recovery from the pandemic.

Inflation rose because of the collapse of global supply and supply chain issues; the increases in salaries/ wages necessary to entice workers back to the labour force; and government stimulus.

The Fed embarked on an aggressive tightening cycle in a bid to bring inflation under control.

Monetary policy has not worked because this is not a normal monetary cycle – it is a fiscal cycle

Government engineered industrial policy that would keep non-residential investment afloat even with high interest rates.

While we expect economic growth to slow, we do not foresee a recession in 2024.

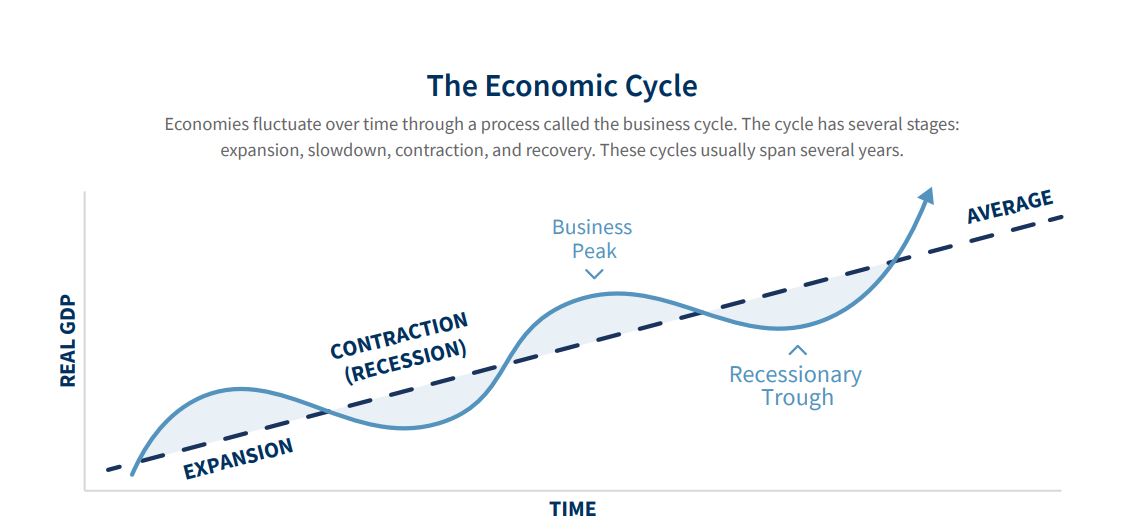

We are normally reluctant to use trendy phrases to explain either our good and/or bad calls regarding the US economy. However, saying that ‘this time is different’ is more than fitting today to understand what has happened to the US economy since the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. US economic growth surprised friends and foes alike during 2023 as both the post-pandemic normalization process continued and the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) attempt to bring down the surge in inflation contributed to the asynchronous performance of the US economy. During a typical economic cycle, as the economy hits the peak of the cycle, the Fed increases interest rates to slow down economic activity to avoid inflation becoming a problem down the road. That is, at the peak of the cycle, resources are fully utilised and thus any further pressure on the utilisation of these resources typically puts upward pressure on the price of these resources. However, this is not what happened at the end of the pandemic. The truth is that prices started to increase for several reasons, but none related to the actual workings of a typical economic cycle.

First, the total collapse of global production during the pandemic reduced the supply of goods while at the same time supply chain issues made the remaining goods very scarce and the acquisition of them extremely expensive. This meant that the increase in the price of the goods was not due to high economic growth but more to the inability to acquire goods cheaply and in a timely fashion. Second, the decline in the labour force participation rate due to the fear of contagion plus all the extra help given by the federal government meant that firms needed to entice workers to return to the labour force through increases in salaries/wages, especially in the service sector of the economy. This also contributed to a further increase in the cost of production and thus in the price of goods and services. Third, the immense amount of federal income transfers during the Trump and early Biden administrations helped Americans accumulate enormous amounts of money at a time when it was almost impossible to spend because the economy was shut down. This money was accumulated during the pandemic and contributed to putting even more pressure on prices as demand for goods skyrocketed during the pandemic while demand for services surged once the US economy reopened after the COVID-19 pandemic ended.

Since price stability is one of the two mandates the Fed has, the other being low unemployment, and one of the only instruments the Fed has to bring down prices is by conducting monetary policy to slow down economic activity, the Fed embarked on one of the most aggressive interest rate campaigns in history to rein in prices.

However, the truth is that traditional monetary policy did not work, and it is still not working. The reason for this is that this wasn’t a normal cycle where a reversal in monetary expansion, i.e., higher interest rates, would help keep economic growth contained or slow down economic growth to keep inflationary pressures at bay. This cycle was created by the COVID-19 pandemic recession as well as by a massive fiscal expansion. Once the production, supply chain, and labour scarcity generated by the COVID-19 pandemic recession were over, the federal government should have taken back, if not completely at least partially, the fiscal expansion created during the COVID-19 pandemic recession.

Of course, this would have been political suicide, so it was not even discussed, let alone implemented.

“The increase in the price of the goods was due to the inability to acquire goods cheaply and in a timely fashion, the decline in labour force participation and fiscal stimulus”

But monetary policy has not been benign during this tightening campaign. The housing markets felt the pain and real residential investment remained in recession territory for nine consecutive quarters. Furthermore, last year’s banking crisis was also triggered by the inability of some banks to adapt quickly to much higher interest rates by adjusting their investments appropriately. Thus, regulators had to intervene and provide liquidity to stop runs on vulnerable institutions.

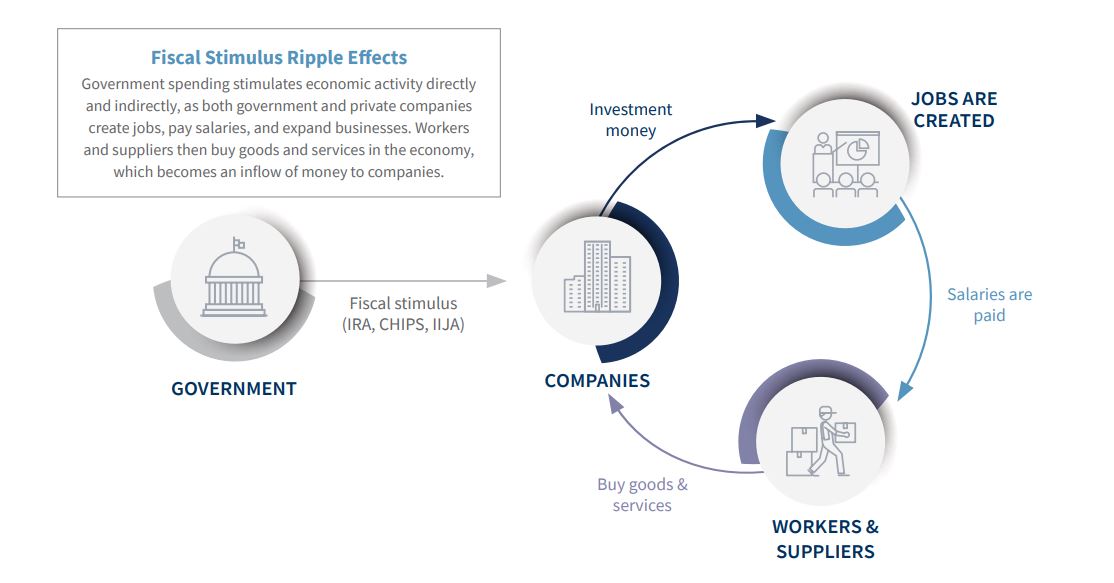

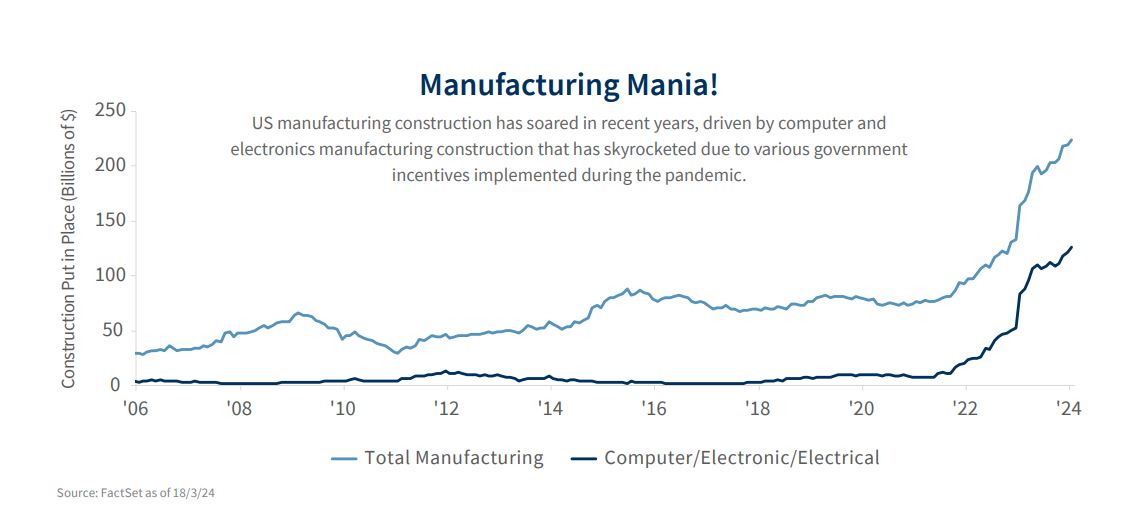

As if this was not enough, after the end of the COVID pandemic, the federal government engineered an industrial policy that would keep non-residential investment surprisingly afloat even under otherwise very high interest rates. Both the passing of the Creative Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) Act, as well as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and, to a lesser extent, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs ACT (IIJA), helped reduce the impact of much higher interest rates on non-residential investment and have contributed to keeping the US economy afloat.

The IIJA is considered a generational investment to rebuild America’s infrastructure, authorizing $1.2 trillion for transportation and infrastructure spending over five years. The bill included $550 billion in new federal spending, with $110 billion for roads and bridges, $47 billion for energy policy, $65 billion for high-speed internet access, $56 billion for airports, and much more. The IIJA was a key component of President Biden’s agenda, but after witnessing the supply chain disruption and shutdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the increase of global geopolitical risk, additional efforts were deemed crucial to both US national defence and other critical sectors of the economy.

While semiconductors were invented in the US, 90% of the world’s supply and 100% of the most advanced chips are currently manufactured overseas. Therefore, two industrial policy statutes were passed in 2022: First, the IRA provides incentives and uncapped tax credits for sustainability projects, clean technology, EV and battery production, and renewable energy such as solar and wind. Second, the CHIPS Act provides $39 billion in direct spending on chip production and 25% uncapped advanced manufacturing tax credits.

The benefits of these large investments trickle down to other sectors of the economy through a process called the government expenditures multiplier. The multiplier measures how much each one dollar increase in spending boosts the country’s economic output, essentially measuring the effectiveness of the government’s effort. While it is very complicated to accurately measure this number due to the multitude of factors impacting the economy at any given time, preliminary data suggests that the three packages have had and will continue to have an outsized impact on the US economy over the next several years. While the US government hasn’t released many funds yet, private companies have already either announced or started making very large investments in building new factories in the US with hopes of benefiting from the various government incentives. Since the pandemic started the combination of these three packages has pushed US manufacturing construction spending higher by 175% to $213 billion per year. Moreover, construction put in place for the manufacturing of computers and electronics has increased by more than 1,000% over the last two years.

The fiscal policies implemented during the pandemic recession helped individuals and firms survive some of the most perilous times in more than a century and helped keep the economy going during the recession. However, many individuals could not spend the funds due to lockdowns and supply chain disruptions, pushing the personal savings rate higher than 30% during the early stages of the pandemic. However, as the limits imposed during the pandemic were lifted and supply chains normalized, the US consumer roared back with lots of excess savings ready to be deployed.

After inflation reared its ugly head during the recovery from the pandemic recession, the Fed could not stand idle and, while late, started raising interest rates. However, few sectors reacted to the increase in rates—mostly residential investment and the housing market—while other sectors were rescued by the three federal government acts that helped keep non-residential investment from reacting to higher interest rates.

The stimulus payments in the hands of individuals and firms, coupled with the effects of the three government acts, rendered monetary policy ineffective. The Fed has increased interest rates to stall and prevent a new monetary cycle from reigniting the inflation fire, but it is currently refraining from further actions until all of these excesses are flushed out of the system.

Consequently, our outlook no longer anticipates a mild recession for the US economy. However, we still expect economic activity to slow down considerably over the next several quarters as high interest rates will continue to keep lending contained. Therefore, while our revised expectations have moved from the mildest recession in US history to a soft landing, our full-year GDP for 2024 has only moved from 1.7% to 2.0%.

“Our outlook no longer anticipates a mild recession for the US economy.”

Issued by Raymond James Investment Services Limited (Raymond James). The value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up, and you may not recover the amount of your original investment. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. Where an investment involves exposure to a foreign currency, changes in rates of exchange may cause the value of the investment, and the income from it, to go up or down. The taxation associated with a security depends on the individual’s personal circumstances and may be subject to change.

The information contained in this article is for general consideration only and any opinion or forecast reflects the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates, Inc. as at the date of issue and is subject to change without notice. You should not take, or refrain from taking, action based on its content and no part of this article should be relied upon or construed as any form of advice or personal recommendation. The research and analysis in this article have been procured, and may have been acted upon, by Raymond James and connected companies for their own purposes, and the results are being made available to you on this understanding. Neither Raymond James nor any connected company accepts responsibility for any direct or indirect or consequential loss suffered by you or any other person as a result of your acting, or deciding not to act, in reliance upon such research and analysis.

If you are unsure or need clarity upon any of the information covered in this article please contact your wealth manager.

APPROVED FOR CLIENT USE