Back to Top ↑

ISQ - October 2024

A tariff is a tax levied on imports. Historically, tariffs have been imposed to generate tax revenue or to protect domestic producers from competition in the form of cheaper foreign goods. In essence, tariffs artificially make domestically produced goods more competitive in the local market by making imports more expensive. At the same time, tariffs allow domestic producers to increase the price they otherwise would have charged for their product had they faced foreign competition. In many ways, trade without tariffs keeps domestic producers’ attempts to increase prices at bay. While tariffs have been utilised heavily in the past, both their usage and rates have fallen considerably over the past half century as countries have engaged in different stages of trade negotiations. Both the volume and value of global trade have grown exponentially as tariffs and barriers to trade have fallen over the decades. This has coincided with the growth of the global economy over the same period, which is, on average and in aggregate, more prosperous than at any time in human history.

In essence, tariffs artificially make domestically produced goods more competitive in the local market by making imports more expensive.

While it is readily apparent that emerging economies have reaped outsized rewards because of freer trade, developed economies as a whole have benefited as well. The availability of cheaper imported goods has enabled consumers in developed economies to retain a larger share of their income for consumption, saving or investment. The same holds true for companies, which benefit from lower input costs and higher profit margins when there are fewer barriers to trade. The strength and dominance of the US dollar as the world’s dominant currency, helped by the sizable and consistent demand for US financial assets, the growth of the US economy, as well as the large fiscal deficits over the years, have all contributed to the increase in US consumption and thus to a sizable increase in imports from the rest of the world. This has created a large current account deficit (this includes the trade deficit in goods as well as the surplus in the trade of services), which must be financed with foreign savings. That is, the rest of the world has essentially financed the expansion of US consumption by purchasing US financial assets and investing in its economy. In exchange, the rest of the world has been buying US physical assets as well as receiving interest and dividend payments from these transactions. Thus far, this arrangement has, on the whole, greatly benefited the US economy and will remain a non-issue as long as the US dollar remains the world’s reserve currency and the US economy the preeminent place to invest.

Trade is almost always better than no trade.

When tariffs are imposed or increased the price of those goods affected rises too, potentially increasing inflation. Goods become more expensive to consumers and inputs become more expensive to companies, reducing both purchasing power and profitability, respectively. That is to say, the aggregate impact to the entire economy at large is negative. Furthermore, if nations engage in a ‘trade war’ wherein each nation retaliates with their own tariffs, which is what happened when the US enacted tariffs the last time, the negative economic effects could be amplified.

Trade is almost always better than no trade. And, as we mentioned above, the process toward freer trade over the last several decades has benefited the world economy as a whole, not only in terms of economic growth but also in terms of allowing countries to benefit from comparative advantage and produce, and export, products they are most efficient at producing. We are not saying that there may be some arguments for the imposition of tariffs, more that those instances have to be considered on a case-by-case basis. The imposition of blanket tariffs as an argument to solve trade imbalances is not a good way to tackle the root cause of these deficits. Sometimes, governments impose tariffs when they think that countries/companies are ‘dumping’ or selling products in the international market at prices that are lower than in their domestic market.

On other occasions, governments impose tariffs to temporarily protect a company that is experiencing short-term issues at home, and politicians deem that the company’s existence is at risk if the government doesn’t intervene. Sometimes a country imposes tariffs if it believes that companies in the foreign country are being subsidised and are improving the competitiveness of their products vis-à-vis domestic companies, etc.

An alternative that can help to reduce the trade deficit, if this was the true reason for the imposition of tariffs, might be to reduce the fiscal deficit. However, this would slow economic activity as well as economic growth and politicians are probably not going to be willing to consider this avenue for improving the trade balance.

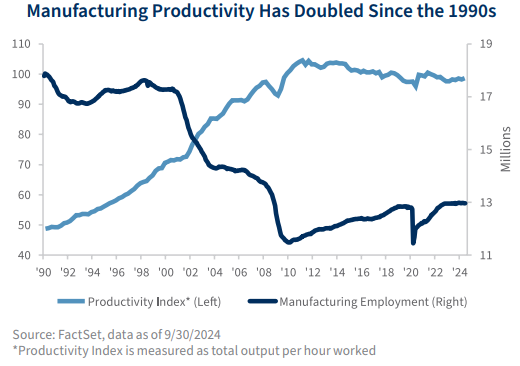

The US manufacturing sector has been transformed over the last several decades as cheaper imports have put pressure on the sector’s competitiveness. Higher manufacturing wages in the US compared to the rest of the world are probably the root cause of such a shift. According to the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), the average salary of a manufacturing worker in the US in 2022 was $98,846, including benefits, compared to about $13,638 in China and $15,804 in Mexico.1 However, the sector’s transformation has meant that it is using more machines and more skilled labour to produce goods and this requires fewer workers to produce than in the past. This means that the sector has continued to specialise in the production of those goods that it is most efficient in producing. That is, although employment in manufacturing has declined by nearly 30% since the 1990s, manufacturing productivity has doubled during the same period. This increase in manufacturing productivity has meant that manufacturing workers are highly paid compared to workers elsewhere in the developed world.

During the Trump presidency the US raised tariffs on many US trading partners, tariffs that the Biden administration has kept almost unchanged. China was affected the most, with over $380 billion worth of steel, aluminium, washing machines and solar panels impacted by tariffs, for a total increase in tariff revenues of ~$80 billion. It has been estimated that the average household has paid an additional ~$300 annually due to the 2018 trade war.

The COVID-19 pandemic, the government’s massive fiscal package, the inflation spike of 2022, and the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) monetary policy journey have certainly overshadowed any impact that the 2018 trade war might have had. However, that’s behind us, pandemic-era excess savings are depleted, inflation is close to the Fed’s target, the central bank has started to ease rates, and we are now staring at the possibility of a new trade war. While trying to estimate the effects of additional tariffs and potential retaliation from foreign countries is an extremely complex task with lots of variables at play, we’ve tried to estimate the potential impact on the US economy from the imposition of a 10% import tariffs on all trading partners and 60% tariffs on all Chinese imports.

Under this scenario, the tariffs will generate ~$500B in revenues, which could, on one hand, have a negative impact on GDP if the revenues from tariffs are not returned to the economy. Typically, higher tariffs are paid by consumers through higher prices for the goods they consume. Furthermore, the impact on consumers, especially those in the lower income quintiles, could be severe as not only are they likely to have fewer options, but may be forced to spend much more as businesses will likely pass the bulk of the price increase to consumers. On the other hand, domestic producers will likely attempt to use the impact of tariffs on imported goods to boost their profit margins by increasing prices of competing domestically produced goods. Overall, if tariff revenues increase more than sixfold (from $80 billion to $500 billion) then the extra amount that the average household will have to pay increases from ~$300 annually to ~$1,900 annually, then that could adversely impact the US economy by as much as 1.9% of total GDP.

If these tariffs are enacted, a trade war is likely to ensue as trading partners retaliate by imposing similar tariffs on US exports. In this escalation, the trade deficit will likely widen further, and US exporters may experience as much as a ~$400B hit on revenues depending on how much the quantity demanded by trade partners might decline. Additionally, if the US dollar were to appreciate in response to the imposition of tariffs, US exporters would have a harder time selling their products overseas, which would likely have a negative impact not only on exports, but also on US production and the labour market.

Inflation is likely to increase as tariffs are implemented and prices increase, but unless the trade war continues over the years, the inflation spike may be short-lived. However, if inflation increases then the Fed may be pushed to either increase interest rates or keep interest rates higher for longer compared to a no-tariff-war scenario or until the effects from the tariffs are pushed through the US economy. It is difficult to know the actual impact on overall inflation, but an across the board increase in tariffs has the potential to push inflation higher.

An across the board increase in tariffs has the potential to push inflation higher.

Those who believe that freer trade is not good for a country typically believe that international trade is a ‘zero-sum game,’ which means that if one country loses, that is, has a trade deficit, then the country with the corresponding, and opposite, trade surplus, is the winner. However, trade is, typically, not a zero-sum game but a ‘positive-sum game’ in which everybody wins by engaging in mutually beneficial commercial endeavour. The idea that a trade surplus is better than a trade deficit comes from the old and discarded theory of ‘mercantilism,’ a view of the world that lasted from the 16th to the 18th centuries and considered the wealth of a nation depended on the size of its trade surplus while limiting imports through the imposition of tariffs.

However, the reality is more complex. As discussed above, trade deficits and surpluses do not necessarily denote whether a nation is at an inherent economic advantage or disadvantage. In this sense, trade is more like a ‘positive-sum game’ with a variety of possible payoffs. Generally speaking, all nations stand to benefit by ‘cooperating’ in an environment of freer trade. However, tariffs and protectionist measures disrupt global supply chains, increasing costs and reducing profitability. In other words, nations stand to be harmed by ‘defecting’ from free trade and engaging in trade wars.

– A tariff is a tax on imports.

– Historically, tariffs have been enacted to generate tax revenue or to protect domestic producers from competition in the form of cheaper foreign goods. Imports are made more expensive so domestically produced goods can be more competitive in the local market.

– When tariffs are imposed or increased the price of the goods rise, potentially increasing inflation. Goods become more expensive to consumers and inputs become more expensive to companies.

– China has been most affected by US tariffs imposed by former President Trump and continued by President Biden.

– In our view, the imposition of further tariffs should be considered on a case-by-case basis, rather than applied as a blanket strategy to decrease a trade deficit.

Issued by Raymond James Investment Services Limited (Raymond James). The value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up, and you may not recover the amount of your original investment. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. Where an investment involves exposure to a foreign currency, changes in rates of exchange may cause the value of the investment, and the income from it, to go up or down. The taxation associated with a security depends on the individual’s personal circumstances and may be subject to change.

The information contained in this article is for general consideration only and any opinion or forecast reflects the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates, Inc. as at the date of issue and is subject to change without notice. You should not take, or refrain from taking, action based on its content and no part of this article should be relied upon or construed as any form of advice or personal recommendation. The research and analysis in this article have been procured, and may have been acted upon, by Raymond James and connected companies for their own purposes, and the results are being made available to you on this understanding. Neither Raymond James nor any connected company accepts responsibility for any direct or indirect or consequential loss suffered by you or any other person as a result of your acting, or deciding not to act, in reliance upon such research and analysis.

If you are unsure or need clarity upon any of the information covered in this article please contact your wealth manager.

APPROVED FOR CLIENT USE