ISQ - April 2022

Key Takeaways

The Federal Reserve (Fed) is the central bank of the US. It was created by Congress in 1913 to prevent financial panics and, over time, its responsibilities have grown.

The Fed’s dual mandate is stable prices and maximum employment, and its primary monetary policy tool is the federal funds rate.

Policy decisions are based on a wide range of information. The Fed doesn’t react to the eco-nomic data per se, but to what the data imply for the outlook ahead..

Monetary policy is akin to steering a supertanker.

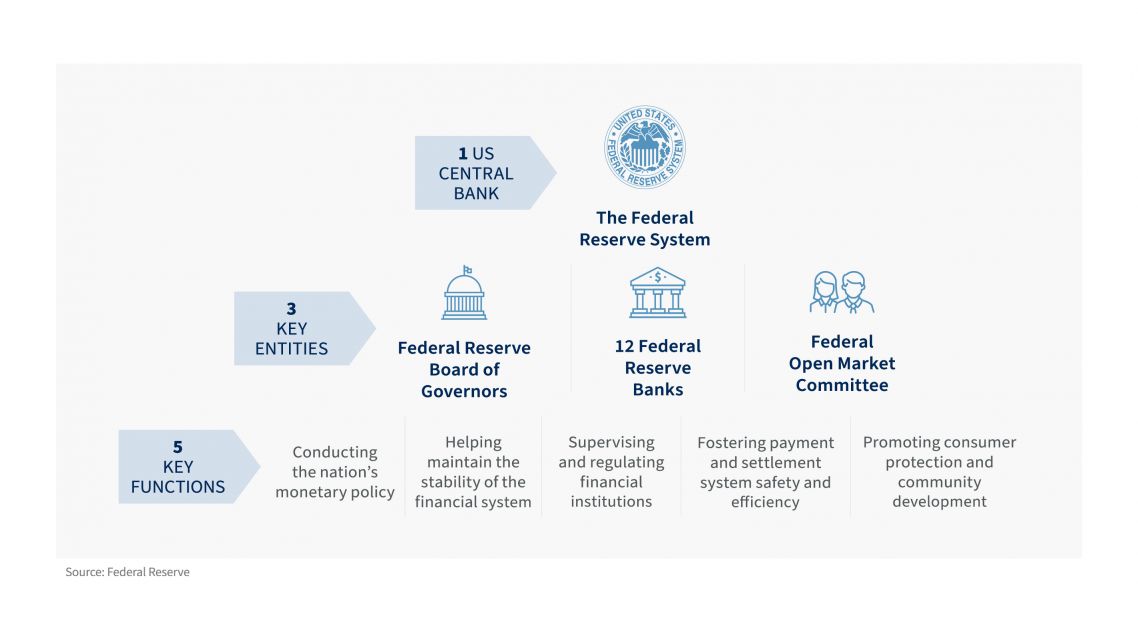

The Federal Reserve (Fed) is the central bank of the US. It was created by Congress in 1913 to prevent financial panics. Its responsibilities have grown over time. While sometimes referred to as the unofficial fourth branch of government, it is quasi-governmental – independent, but answerable to Congress. The Fed is made up of the seven-member Board of Governors in Washington, DC and 12 Federal Reserve Banks around the country. The Fed governors are appointed by the president and confirmed by Congress, with terms of 14 years. The Chair, Vice Chair, and Vice Chair of Supervision (also governors) are appointed to four-year terms. The 12 regional bank presidents are appointed by the boards (composed of private citizens) of each of their individual banks.

One of the Fed’s main tasks, and the one most critical to financial markets, is monetary policy – the setting of short-term interest rates to achieve the optimal performance of the economy. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), made up of the Fed governors, the New York district bank president, and four other district bank presidents (who rotate in January), sets monetary policy. While only FOMC members vote on monetary policy, all senior Fed officials participate at policy meetings.

The Fed also supervises and regulates banks, promotes consumer protection and community development, and works to ensure stability in the financial system. The Fed acts as a bank to other banks, clearing checks, making electronic payments, and providing currency.

In regard to monetary policy, the Federal Reserve Act states that the Fed “shall maintain long-run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long-run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.”

The Fed interprets “stable prices” as low, but positive, inflation. This gives the Fed some room to support the economy with low interest rates during a recession and allows inflation-adjusted wages to adjust downward during periods of economic weakness.

In January 2012, the Fed followed other central banks in formally adopting a 2% inflation target (as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index), although it had an implicit target of 1.7% to 2.0% before that.

The employment goal is maximum sustainable employment. There is no specific target for the unemployment rate. The belief has been that using monetary policy to push the unemployment rate lower would eventually lead to inflationary pressures. In fact, the dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment is taken largely as a single operational objective – the job market will perform better over the long run if inflation is low and stable.

After a comprehensive public review, the Fed revised its monetary policy framework in August 2020. One problem with the 2% inflation goal was that it was seen by the markets as a ceiling rather than a target. As a consequence, inflation would average less than 2%. In the revised framework, the Fed moved to a flexible average inflation-targeting system. The long-term inflation goal remains at 2%, but following a period with inflation below 2% (as in the pre-pandemic years), the Fed would seek a period with inflation moderately above 2%. Needless to say, the timing of the shift in the framework was terrible (given the increased inflation pressure seen over the last year).

The dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment is taken largely as a single operational objective – the job market will perform better over the long run if inflation is low and stable.

The Fed recognises that these goals may sometimes be in conflict. Under such circumstances, the Fed will make a judgement call based on how far away it is from each individual goal, and how long it would take to reach those goals.

The primary tool for monetary policy is the federal funds rate, the overnight lending rate that banks charge each other for borrowing reserves. Reserves are balances held at the Fed to satisfy banks’ reserve requirements. Banks with excess reserves can lend them to banks that need larger reserves. The federal funds rate is a market rate. The Fed sets a target range and performs open market operations (buying or selling Treasury securities) to achieve it (hence, the name ‘Open Market Committee’). The federal funds rate (and where it appears to be headed) affects longer-term interest rates. In raising the federal funds rate, the Fed ‘tightens’ the availability of credit. Lowering the federal funds rate ‘eases’ credit conditions.

The primary credit rate (sometimes still called the discount rate) is the rate that the Fed charges banks for short-term borrowing. The Fed’s Board of Governors approves (or not) a request for a change in the primary credit rate made by one or more of the federal district banks. Typically, the primary credit rate is changed at the same time as the federal funds target. Note that the FOMC only began to announce changes to the federal funds target in 1994. Before that, the discount rate, a posted rate, was viewed as the main policy signal.

The Fed sometimes employs forward guidance, a conditional commitment to keep the federal funds rate low for a certain period of time or until some economic objective has been achieved. These promises help to keep long-term interest rates low, promoting growth.

During the 2008 financial crisis, the FOMC lowered the federal funds target range to 0-0.25%. Seemingly out of ammo, the FOMC began its first Large-Scale Asset Purchase program (LSAP), which is more commonly called quantitative easing (QE). In quantitative easing, the Fed buys large amounts of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities each month. The Fed employed QE1, QE2, and QE3 in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and restarted asset purchases on a massive scale in the early stages of the pandemic. The Fed’s asset purchases helped lower long-term interest rates, although they seemed to become less effective at each stage. Unwinding the balance sheet will work in the opposite way, raising long-term interest rates.

The Fed’s asset purchases have ballooned the size of its balance sheet to nearly $9 trillion (it was below $1 trillion before the financial crisis and around $4 trillion before the pandemic). The FOMC expects to begin unwinding its balance sheet later this year. That will occur naturally over time, as the FOMC reinvests a portion of maturing securities. The FOMC does not plan to sell securities out of its portfolio outright, although it will be buying and selling across maturities as the size of the balance sheet declines. The ultimate size of the balance sheet is uncertain; however, it will be based on maintaining an adequate level of reserves in the banking system.

In theory, monetary policy uses the money supply to influence employment and inflation, but the money supply plays no role in policy decisions. As Chair Powell testified in 2021: “The connection between monetary aggregates and either growth or inflation was very strong for a long, long time, which ended about 40 years ago. It was probably correct when it was written, but it’s been a different economy and a different financial system for some time.”

Policy decisions are based on a wide range of information. The Fed doesn’t react to the economic data per se, but to what the data imply for the outlook ahead. Economic data are subject to statistical noise and seasonal adjustment quirks and are often revised. The Fed also relies on anecdotal information collected by the district banks to gauge labour market conditions and inflation pressures.

The FOMC arrives at its policy decisions by consensus. Officials are in touch with each other before policy meetings and a decision rarely hasn’t been worked out in advance. Occasionally, one or two FOMC members may formally dissent in favour of tighter or looser policy.

Monetary policy affects the economy with a long and variable lag. It may be a year or more before the full effects of a policy change are felt. Hence, monetary policy is akin to steering a supertanker. Policy changes tend to be gradual. However, rate cuts tend to come faster than rate increases.

The Federal Reserve is firmly committed to achieving the goals that Congress has given it. Inflation remains elevated, reflecting supply and demand imbalances related to the pandemic, higher energy prices, and broader price pressures. On March 16, the FOMC raised the federal funds target range by 25 basis points (to 0.25-0.50%) and signalled a more aggressive outlook on rate hikes into 2023. Of the 16 senior Fed officials, 12 anticipated raising the federal funds target range by an additional 150 basis points or more by the end of this year, and most expect another 75 basis points or so in 2023. However, none of this is written in stone. In his press conference following the FOMC meeting, Chair Powell admitted that, in hindsight, the Fed should have begun tightening policy sooner. Powell indicated that the FOMC could raise rates more quickly if appropriate. If inflation fails to moderate as the Fed anticipates, we could see much tighter monetary policy in the months ahead.

The oil shocks of the 1970s and early 1980s are associated with recession as well as higher inflation. While higher oil prices do not cause recessions, in the past, the Fed reacted to higher oil prices by raising interest rates and tighter monetary policy led to recession. Fed policymakers now know that the central bank should not respond to temporary supply shocks. However, because monetary policy affects the economy with a lag, there is a chance of overdoing it and raising rates too much, possibly leading to a recession in 2023, but the odds of that are still relatively low. In the early 1980s, the Volcker-led Fed purposely steered the economy into a recession to reduce inflation. A similar outcome may be possible in the current situation, but inflation was much higher in the early 1980s and long-term inflation expectations have remained well anchored.

Issued by Raymond James Investment Services Limited (Raymond James). The value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up, and you may not recover the amount of your original investment. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. Where an investment involves exposure to a foreign currency, changes in rates of exchange may cause the value of the investment, and the income from it, to go up or down. The taxation associated with a security depends on the individual’s personal circumstances and may be subject to change.

The information contained in this document is for general consideration only and any opinion or forecast reflects the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates, Inc. as at the date of issue and is subject to change without notice. You should not take, or refrain from taking, action based on its content and no part of this document should be relied upon or construed as any form of advice or personal recommendation. The research and analysis in this document have been procured, and may have been acted upon, by Raymond James and connected companies for their own purposes, and the results are being made available to you on this understanding. Neither Raymond James nor any connected company accepts responsibility for any direct or indirect or consequential loss suffered by you or any other person as a result of your acting, or deciding not to act, in reliance upon such research and analysis.

If you are unsure or need clarity upon any of the information covered in this document please contact your wealth manager.

APPROVED FOR CLIENT USE