Back to Top ↑

Key Takeaways

The pandemic crisis tentatively has caused a rethinking of previous orthodoxies and hardened negotiating instincts.

Influential has been Germany’s shift from a balanced budget position to, at least temporarily, a material deficit position.

There has never been a clearer opportunity to push the button on a pan-regional fiscal policy initiative.

Such a policy could induce a reassessment from global asset allocation specialists to the region’s financial markets and the Euro.

‘‘In the midst of every crisis, lies great opportunity”

Albert Einstein

Despite this unpromising backdrop, the pandemic crisis tentatively has caused a rethinking of previous orthodoxies and hardened negotiating instincts. And whilst the heavy toll across families and broader populations throughout all western European countries – but especially Italy and Spain – will not be forgotten, the crisis of yet another period of economic growth challenge has led to some surprising reactions.

Christine Lagarde’s first few weeks as President of the ECB did not get off to a particularly smooth start, with a fumbled answer about sovereign bond spreads in her inaugural press conference inducing volatility in the deeply influential Italian bond market. Lagarde’s years as head of the International Monetary Fund, however, put her in a good position to both help forge compromises and respond to a burgeoning crisis by further heightening and extending the central bank’s quantitative easing policies.

So far, so textbook. The Eurozone’s problems have never been with its central bank since the previous president Mario Draghi’s ‘whatever it takes’ Damascene conversion. Such willingness to embrace an extended balance sheet has created powerful enemies over the years. Whilst the German Bundesbank maintained a policy of tentative and mild support at best, the country’s Constitutional Court materially upped the ante in May by calling the ECB’s bond-buying powers into question.

It goes without saying that this was at face value extremely unhelpful. However, acute observers would have noted at the time the frustration towards the court espoused by German Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose final years of direct political power have been riven with challenges. Last autumn my own conclusion was that the impending chancellorship election due two-thirds of the way through 2021 would induce her own Damascene conversion to a world of legacy enhancing unbalanced fiscal budgets. The conclusion was correct, but the transmission mechanism to get there was very, very different.

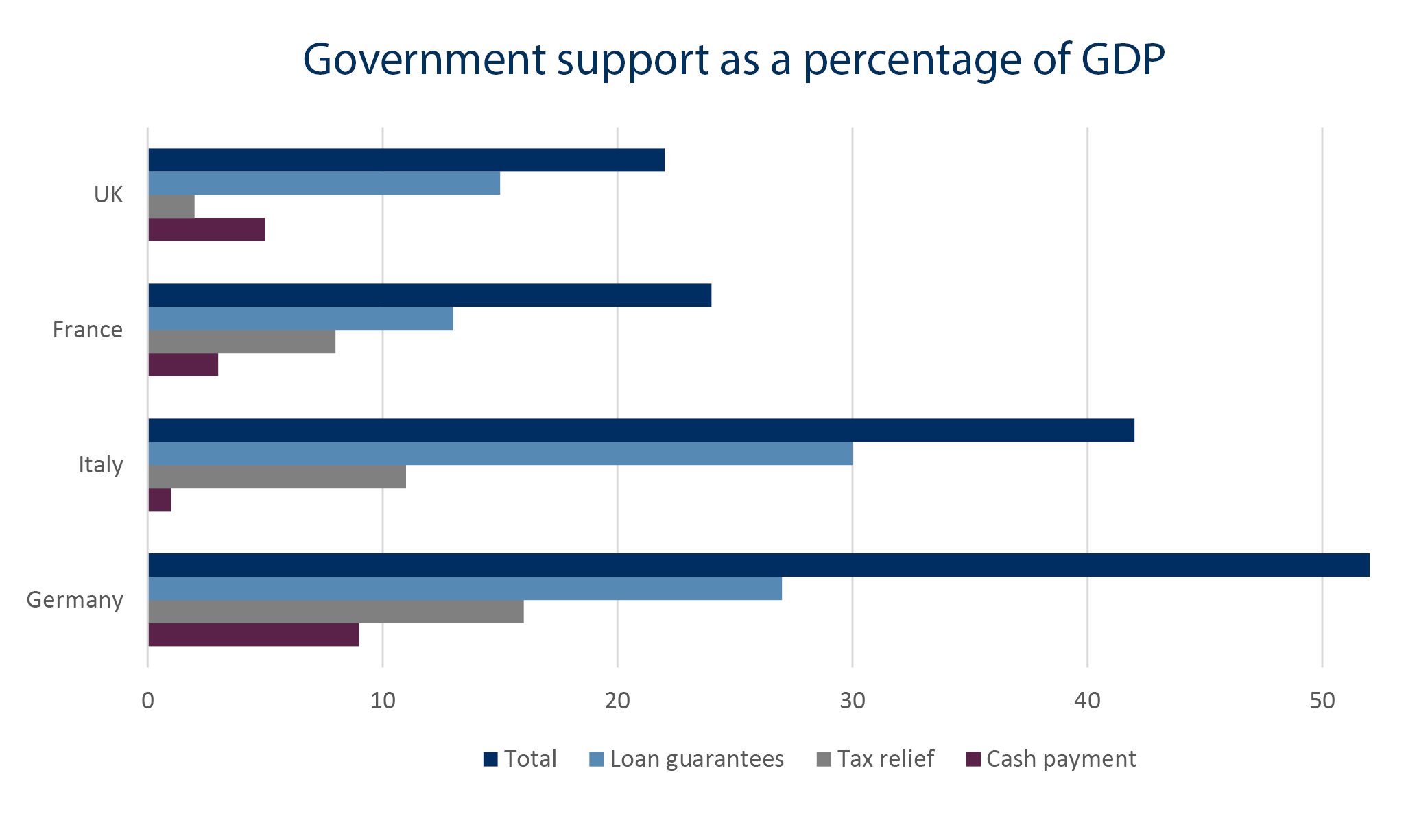

Possibly influenced by her own scientific background but certainly backed by an efficient and effective administration, the German pandemic response has impressed many neutral observers. Looking beyond the bald healthcare numbers and statistics, Germany was also most proportionately responsive in areas such as loans and associated financing opportunities to business to tide them over the pandemic period. Certainly, there is something about a truly exogenous crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic that highlights, even to a country that prides itself on business efficiency and high productivity, that material assistance – even of an anticipated temporary nature – is required. Supplement this with the costs of a wage support scheme and Germany’s very orthodox balanced budget position had shifted, at least temporarily, to a material deficit position.

Contrary to the instincts of many arch Euro-sceptics, the really big heavy lifting fiscally across Europe is still undertaken by the national governments. Unsurprisingly, the crisis has produced a slew of national government fiscal initiatives boosting budget deficits to levels that would have provoked anger and sanctions at previous crisis times in the Eurozone. At this time, supplemented by the ECB’s continued efforts, these are being funded at strikingly low bond yields. Whilst this may appear to reflect a coordinated monetary and fiscal policy, the dearth of a central fiscal lever sourced straight out of Brussels and used as a supplementary fiscal boosting tool in the most impacted parts of the whole Eurozone, was missing. Such pan-regional fiscal rebalancing is a function of all successful monetary unions (for example the United States). Recent weeks have seen plans and actions – led by Angela Merkel – to forge the first of these instruments. With Germany holding the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union until the end of 2020, there has never been a clearer opportunity to push the button on such an initiative. Again, this is no panacea, but it reflects both the Eurozone and the European Union continuing to grow up. It is just a shame that it took such a crisis to open up such a potential policy shift.

Meanwhile, for asset allocation experts whose default position has been to underweight both the region’s financial markets and the Euro, it should induce a reassessment. ‘In the midst of every crisis, lies great opportunity’.

Issued by Raymond James Investment Services Limited (Raymond James). The value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up, and you may not recover the amount of your original investment. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. Where an investment involves exposure to a foreign currency, changes in rates of exchange may cause the value of the investment, and the income from it, to go up or down. The taxation associated with a security depends on the individual’s personal circumstances and may be subject to change.

The information contained in this document is for general consideration only and any opinion or forecast reflects the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates, Inc. as at the date of issue and is subject to change without notice. You should not take, or refrain from taking, action based on its content and no part of this document should be relied upon or construed as any form of advice or personal recommendation. The research and analysis in this document have been procured, and may have been acted upon, by Raymond James and connected companies for their own purposes, and the results are being made available to you on this understanding. Neither Raymond James nor any connected company accepts responsibility for any direct or indirect or consequential loss suffered by you or any other person as a result of your acting, or deciding not to act, in reliance upon such research and analysis.

If you are unsure or need clarity upon any of the information covered in this document please contact your wealth manager.

APPROVED FOR CLIENT USE